Cognac: Where Terroir, Technique & Time Collide

Cognac isn’t just another aged spirit tucked away on the back bar. It’s a living system — soil, grape, distillation, and aging — bound together by some of the most rigorous rules in the drinks world.

Its survival through vineyard collapse, its obsession with chalky soil, and its ability to adapt without losing its soul make it one of the most fascinating spirits you can study or pour. If you’re going to sell Cognac, serve it, or even sip it with intent, you need to understand why it tastes the way it does. And that story runs through history, terroir, yeast strains, copper stills, and the oak of a damp Charente cellar.

A Short History: Cognac’s Collapse and Rebirth

The Cognac region didn’t set out to make a luxury spirit. Its wines, fragile and acidic, couldn’t survive export. Dutch traders distilled them into brandewijn for stability, and locals refined the technique. By the 17th century, double distillation had become standard, producing an eau-de-vie elegant enough to rival fine wines.

By the 18th century, Cognac was a global luxury, led by names like Martell, Rémy Martin, and Hennessy. But in the late 1800s, phylloxera (an aphid imported from America) devastated 85 per cent of the vineyards. The recovery came through grafting French varietals onto American rootstock, and by shifting to Ugni Blanc, a workhorse grape that didn’t shine in the glass but proved perfect for distillation. The crisis reshaped Cognac’s identity, embedding resilience into its DNA.

The BNIC: Guardian of Tradition and Innovation

Since 1946, the Bureau National Interprofessionnel du Cognac (BNIC) has been the region’s referee, marketer, and futurist. The BNIC sets the rules: which grapes can be planted, how many vines per hectare, which yeast strains are allowed, when fermentation and distillation must be complete, and even how Cognac can be aged and bottled.

Think of it as Cognac’s central nervous system. Without the BNIC, Cognac would have splintered into inconsistent brandies decades ago. With it, the spirit maintains global credibility while still leaving room for innovation, from sustainability initiatives to promoting single-estate bottlings.

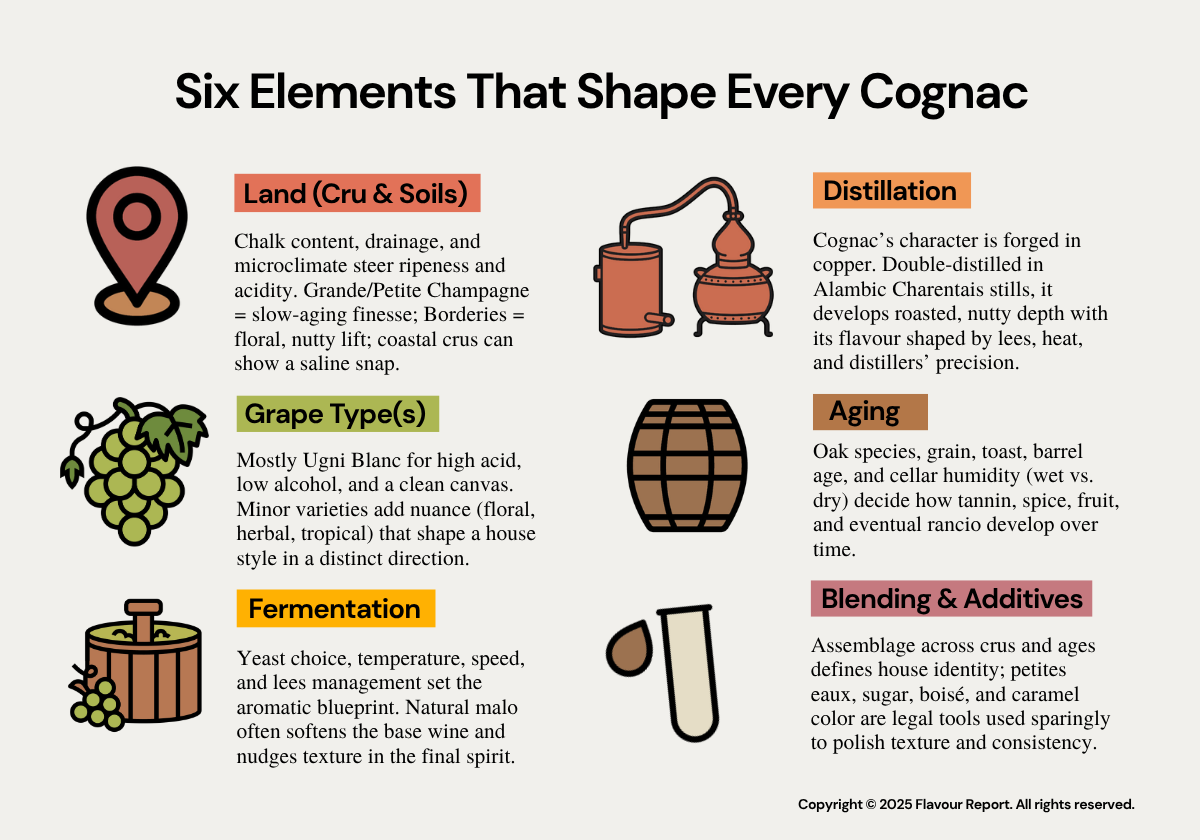

Six Elements That Shape Every Cognac

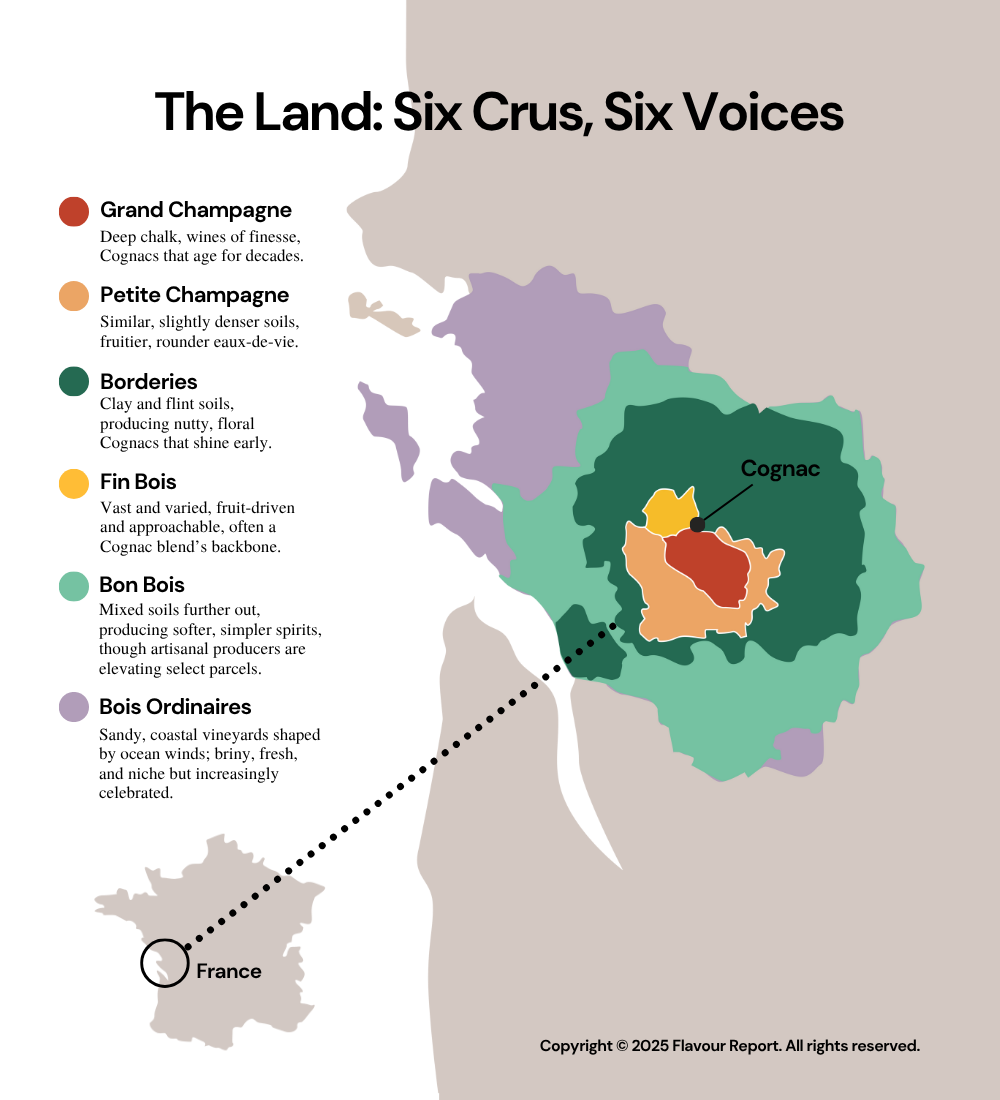

Behind every bottle of Cognac lies a network of decisions that make one house’s style unmistakable from another. The BNIC provides the structure, but the soul of Cognac is formed through six key forces: the land it grows from, the grapes that define its base, the fermentations that shape aroma, the distillation choices that sculpt texture, the aging that deepens character, and the blending that ties it all together. Understanding these factors is the key to tasting Cognac not just as a spirit but as an ecosystem.

The Grapes: Ugni Blanc (& Friends)

Ugni Blanc dominates Cognac because it gives what distillers need: high acidity, low potential alcohol, and neutral fruit that distills clean and ages gracefully. A few permitted supporting actors show up in tiny volumes:

Folle Blanche: Highly aromatic and floral; beautiful but fragile in the vineyard.

Colombard: Zesty acidity with citrus and tropical hints; lifts blends.

Folignan (Ugni × Folle): Designed for aroma; used sparingly for perfume/aromatics.

Montils & Sémillon: Rounder, waxy textures in small doses.

Jurançon Blanc & Meslier St-François: Rare heritage grapes that add subtle complexity.

Pick timing skews early to preserve acid, no chaptalization, and the goal is a lean, tart base wine that sings in copper and ages into character.

Fermentation: The Forgotten Stage

Before copper stills ever see a drop of wine, fermentation sets the stage. Grapes (as mentioned mostly Ugni Blanc) are pressed into juice, then converted into a sharp, low-alcohol wine of about eight to nine per cent ABV.

Here the BNIC steps in: only 14 approved strains of yeast may be used, and no sugar additions are allowed. These rules preserve both typicity and transparency. The result is a dry, acidic wine unfit for the table but perfect for distillation.

Often, malolactic fermentation occurs naturally. This secondary fermentation softens the wine’s biting acidity, swapping malic acid for lactic acid, creating a smoother, rounder base. That subtle shift is crucial, as it influences texture and balance in the distillate.

Distillation: Copper, Flame, and the Maillard Effect

Cognac’s signature character comes from its stills: the Alambic Charentais, bulbous copper pots heated over an open flame. The process is always double distillation (à repasse):

First run: the première chauffe, producing brouillis (28–32 per cent ABV).

Second run: the bonne chauffe, where only the heart (68–72 per cent ABV) is kept. The heads and tails are cut away or recycled.

Here’s where artistry matters. Distilling on the lees (with dead yeast sediment) gives a creamier, savoury depth; off the lees yields lighter, fruitier spirit. Each house chooses its path.

And let’s not skip the chemistry. Open-flame distillation triggers the Maillard reaction, the same browning that makes seared steak taste rich. Sugars and amino acids from the wine react on hot copper surfaces, producing roasted, nutty, caramelized notes. It’s flavour you can’t fake, and it’s part of why Cognac doesn’t taste like any other brandy on earth.

Aging: Where Oak and Cellar Shape the Spirit

Fresh eau-de-vie is clear, fiery, and sharp. Oak barrels and time transform it. Cognac’s AOC laws require at least two years in oak (not necessarily French), typically from the Limousin (loose-grained, bold, spicy) or Tronçais (tight-grained, subtle, elegant) forests in France. But oak is only half the story. The cellar environment (called chai) dictates how Cognac matures:

Dry cellars – Lower humidity, higher evaporation of water, raising ABV and producing intense, structured flavours.

Wet cellars – Higher humidity, faster alcohol evaporation, giving softer, rounder textures.

Producers rotate casks between to find balance. Over time, oxidation transforms raw spirit into layers of fruit, nuts, spice, and eventually rancio which is the term for the deep, savoury hallmark of old Cognac. And always in the background, the part des anges (or angel’s share) causes about 2 per cent evaporation of the liquid from the barrels each year. This in turn concentrates what remains.

Blending and Additives: The House Style

Blending is where Cognac becomes more than the sum of its parts. The maître de chai (cellar master) tastes through hundreds of eaux-de-vie, combining Crus, vintages, and cellar influences to build the house style.

Two key terms matter:

Assemblage – The creation of the blend.

Élevage – The nurturing of that blend as it continues to evolve in barrel or glass container.

To refine texture and consistency, a handful of additives are legal: water or faibles (which is essentially a low-strength version of eau-de-vie) for dilution, sugar (up to 2 per cent) for balance, boisé (oak extract) for structure in younger blends, and caramel colouring for consistency. These aren’t cheats; they’re part of the Cognac toolkit, used with restraint to ensure each bottle reflects both terroir and house identity.

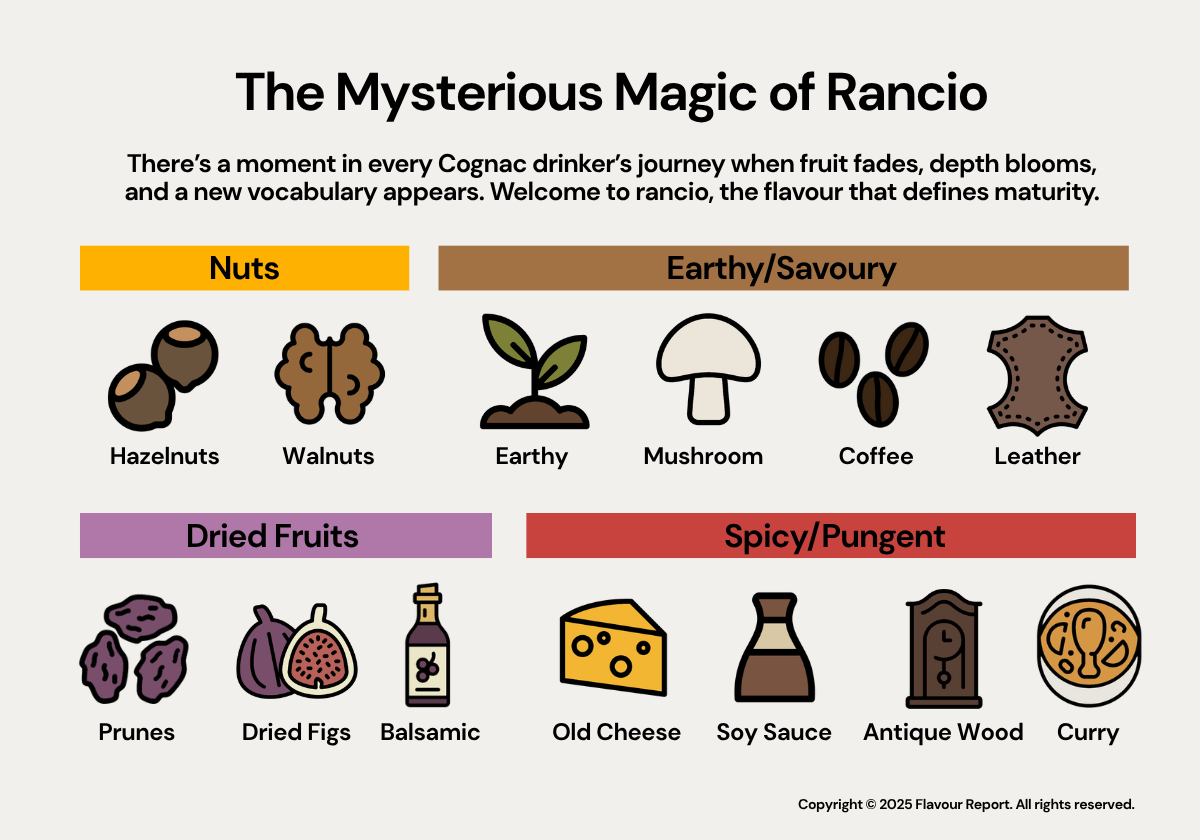

What is Rancio de Charentes?

If you hang around Cognac geeks long enough, you’ll hear the word rancio tossed around like it’s some secret handshake. And honestly, it kind of is.

Rancio de Charentes isn’t an ingredient, a grape, or a cellar technique, it’s a flavour phenomenon. It’s what happens when Cognac ages long enough (we’re talking 15, 20, 30+ years in oak) for oxygen, oak tannins, and time to team up and transform bright fruit into something deeper, nuttier, and more savoury. Think walnuts, mushroom, leather, curry, even blue cheese funk. They’re flavours you’d never expect in a brandy but that make old Cognac so unique and compelling.

The magic is oxidative aging. Younger Cognacs give you floral notes and fresh fruit. As decades roll on, those compounds break down and reform into savoury, almost umami-like aromas. People don’t always perceive it the same and it’s not always consistent. Some tasters get earthy truffle, others dried fig, soy sauce, or antique wood. It’s the spirit evolving past “delicious” into “mysterious.”

Here’s the kicker: rancio doesn’t show up in every Cognac. The cellar environment, the type of oak, the cru, and the master blender’s patience all matter. So next time someone mentions rancio, don’t nod like you know, lean in, sip slow, and taste what decades of patience can create. That’s the soul of old Cognac.

History in a Glass

Cognac is both fragile and indestructible. Fragile because it almost disappeared in the phylloxera years. Indestructible because it came back stronger, with the BNIC, strict AOC protections, and producers who understand how to balance terroir, technique, and time. When you pour it, you’re not just pouring a spirit, you’re pouring a survival story, a masterclass in blending, and a taste of a region that has spent centuries perfecting its craft. That’s why Cognac deserves more than a casual nod behind the bar. It deserves respect.